COVID-19: Looking Back and Looking Forward

This article is part of our long-running COVID-19 Virtual Conversation series from the Institute of Science & Policy in collaboration with the Colorado School of Public Health. Find all series episodes on our YouTube channel.

Now that we have reached the three-year mark of living with COVID-19 in the US, public health experts are reflecting on the past and the path forward. For COVID-19: Looking Back and Looking Forward we discuss long COVID, plus review what we’ve learned about the virus, what has changed, and what the future may hold. Institute Director Kristan Uhlenbrock spoke with Dr. Rachel Herlihy, State Epidemiologist at the Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment; Dr. Jerry A. Krishnan, Associate Vice Chancellor for Population Health Science and Professor of Medicine and Public Health at University of Illinois Chicago; and Dr. Jonathan Samet, Dean of the Colorado School of Public Health, for a wide-ranging discussion on lessons learned about the virus from public health communication challenges and the erosion of trust in science to long COVID, ongoing data collection, and testing.

Looking back

KRISTAN UHLENBROCK: I'm the director of The Institute for Science & Policy, a project here at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, and I'm thrilled to be bringing you episode number 35 in our COVID-19 series that we've been doing in partnership with the Colorado School of Public Health. A huge thank you to them for this long-standing collaboration and the opportunity to bring you these really thoughtful and informed talks for the three years we've been living with COVID-19.

I think it was March 11th that the World Health Organization declared it a global pandemic. March 13th here in Colorado holds a lot of significance for many of us as we saw our government functions start to shut down, and we saw many of our offices closed. I know many of us went home on March 13th really scared and looking forward to understanding what was happening with this pandemic. Here we are three years later and we're bringing you some thoughtful public health experts, and we're going to do a little bit of that reflective retrospective on where we've come in the past three years and what does that path forward look to us.

Introducing my guests:

Dr. Rachel Herlihy, our state epidemiologist here in Colorado. She works for the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment where she leads our COVID-19 surveillance case investigation and outbreak response activities.

Dr. Jerry Krishnan is the associate Vice Chancellor for Population Health Science and a professor of medicine and Public Health at the University of Illinois Chicago. Dr. Krishnan studies new treatment strategies for COVID including long COVID which we will talk about today.

Dr. Jon Samet is a pulmonary physician and epidemiologist. He is the dean of the Colorado School of Public Health. His research is very extensive but also focuses on public health impacts from inhaled and pollutants, chronic disease, infection and just global health in general.

KU: Jon, why don't I start with you. Set the stage looking back at COVID-19 over the past three years regarding some of those cases and hospitalizations that we've seen globally and here in Colorado.

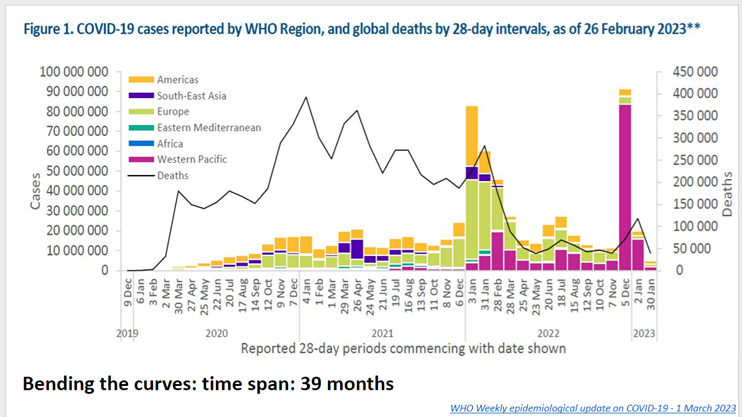

DR. JON SAMET: March 13 was an important day on this campus. It's when the chancellor, Don Elliman sent out a note saying that we would be going to remote operations. This date will stick with me just as a reminder of where we started and where we have come to. Here (Figure 1) are WHO figures showing the estimated number of cases by region. For those of you don't know the regions, the Western Pacific which is lighting up towards the end, that includes China which of course is having now, because of its policies, a very late surge after relaxing the zero COVID policy that they had in place before. You can see the tragedy of the millions of deaths in the black line that we have sustained.

Figure 1

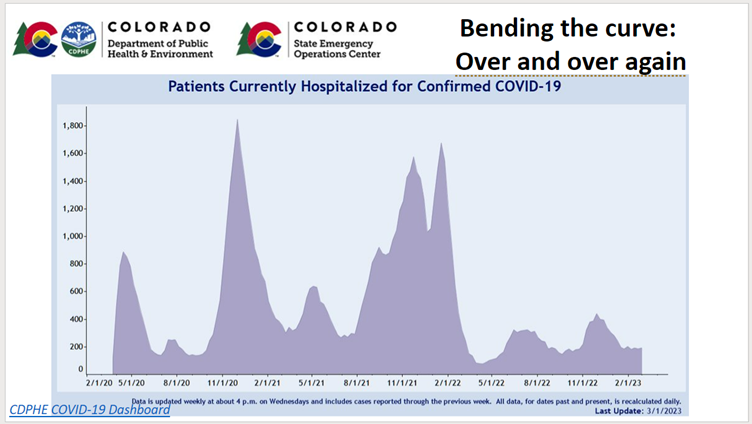

Now lets look at Colorado patients hospitalized for confirmed COVID-19 going back to the start (reference fig 2). I think those of us who have tracked this closely will remember, with a lack of fondness, these peaks that had us so worried over time as we came up to as many as 1,800 Coloradans hospitalized with COVID-19. In terms of assuring health care capacity, we did not want to get over the approximate 2,000 mark and as you can see we flirted with that very alarming level on several occasions. As you go through this you can see the surges that we've sustained. You can see that later on as we had vaccination, and with Omicron we had a surge of cases and a rise in hospitalizations but nowhere near the levels that we experienced earlier for example with the Delta variant. We've had our ups and downs, and we've brought into play a variety of measures to control the pandemic including that initial phase when we were staying at home. We are now in a different phase but if you look out to the end, there are still people hospitalized with COVID-19 and that number has been roughly around 200 over the last several months. We would like to think that the pandemic is over in Colorado, but it isn't and clearly we've gone on to a new phase. One that feels far less scary than on March 13, 2020.

Figure 2

KU: Rachel, start with how has our response changed from those early days to where we are now and why. What are some of those things that we've done that you've reflected on over the past three years?

DR. RACHEL HERLIHY: As Jon described, really since the beginning of the response, our hospital capacity has been guiding our response, wanting to ensure that we had sufficient health care capacity available to Coloradans. And that was whether you needed a hospital bed for COVID-19 or because you were in a car accident or had a heart attack -- we wanted Coloradans to have access to the health care they needed. That was our guiding force and a lot of the effort that we put into modeling and trying to project what the course of the pandemic was going to look like here in Colorado.

We obviously saw a very dramatic shift in the tools in our toolbox to respond to the pandemic from the very beginning where individuals were staying home. We were still learning about masks. And then obviously a vaccine became available and we saw much greater levels of immunity. As time went on we also saw the virus change, so not only did we change, our immune systems changed. We had been exposed to vaccines multiple times, and we had been exposed to infections over time so we had much higher levels of immunity. But the virus changed too so we saw the virus become more transmissible, so more easily spread from person to person but resulting in less severe disease.

The next really important change that we saw in the evolution of our response was the introduction of effective treatments, so a treatment that could now dramatically change the course of individuals who had access to that treatment, preventing hospitalization. Some of the data that we know about Paxlovid is that somewhere between 50 and 80 percent of hospitalizations can be prevented for individuals that received that treatment early. So really dramatic shifts that adjusted how we were responding and the guidance that we were providing to Coloradans and across the country.

KU: Jerry, I want to bring you into this conversation. Rachel just brought up Paxlovid and I have read about the rebound effect of Paxlovid. What are we seeing in regards to that treatment?

DR. JERRY KRISHNAN: We're still learning how best to manage the infectious disease and I have to say that Paxlovid has been a game changer in most cases. We have really dramatically shifted the curve towards less severe disease. What we are seeing though is that there are some people that can tend to get sick once they finish Paxlovid and we're not entirely sure what that's about. There's some theories that perhaps there are areas of the body where the virus hasn't been completely controlled and so the virus is almost sequestered and maybe we need a longer course of Paxlovid. In other cases, it seems like the immune system for some reason gets activated and actually creates trouble. It's almost like the body's attacking itself. There's an autoimmune phenomenon that's happening. So there's a lot of theories right now. But if you look at the big picture Paxlovid is a good thing for people who need it. It's dramatically shifted how sick people have gotten, preventing a lot of hospitalizations that would have otherwise occurred. And now we're starting to understand what else should we be doing. Should we be thinking about a longer course of Paxlovid? Are there other treatments?

RH: I think that was a fantastic summary. I would just like to add that rebound also occurs in individuals who never receive treatment so that phenomenon is also possible. It's been seen with multiple other treatments as well so it does seem to be something that can happen. I certainly don't want it to be a reason that people choose to not receive treatment -- that would obviously be very detrimental if people choose to not receive treatment because of this potential of a rare rebound occurring.

Lessons learned

KU: Jerry, you're in Chicago, how have you seen the response change either in the public health field or through your own work that you've been doing?

JK: The state of Illinois, in many perspectives is similar to the state of Colorado in that we have urban centers, we have semi-urban, and we have rural areas. One of the hallmarks is that COVID is a hyper local phenomenon. In some places it's a bigger problem than others but if you look at it statewide we certainly are in a situation that's very similar to what Jon just presented. Low rates of hospitalizations, but still very much there, they're not gone. I see these patients in clinic and they come and see me after they've been hospitalized so they're still there, but far fewer than in the past. The southern part of Illinois now is having a higher risk area than the northern part of Illinois, so there's these regional differences that vary.

I think one of the big lessons learned here is that you got to really talk with the public health officials about what they're seeing, their trends, and getting local data is important in order to make some informed decisions about what is reasonable and not reasonable to be doing. What's happening in New York City may or may not be relevant to Chicago, or may or may not be relevant to Peoria in Illinois. But they're also all relevant and public health departments are working super hard in order to stay informed. So this is a grand testament to the need for the United States to support and sustain our public health infrastructure. In Illinois we're viewing this as an example of what could go wrong with global pandemics. Most of us think this is probably going to happen again, though it's hard to predict when so a lot of thinking now is about what are the big lessons learned and how do we prepare for the next one?

KU: What had been a little bit of a lightning rod issue for many regions and localities and states is the idea of masking. And we know not only has our understanding of the value of masking changed, how they can be used and where they should be used, and that masks work to help prevent that spread of disease or the virus. We also know that there's been some questions and research into understanding whether a mask mandate was the most effective way to get people to wear masks and to slow the virus of the spread.

Jon, I'll start with you for comment about the role and evolution of learning how masks help prevent the spread, and touch on the behavioral considerations about mask mandates. Was that a good tool in our toolbox?

JS: I think there's a few things we can say with certainty. I'm going to group under masks the sort of medical masks that people wear and official barrier face coverings, but then also there are respirators, N95, and KN95 that are designed to protect people from inhaling small particles. What the law refers to as masks, using the loose terminology, certainly helps to prevent the immediate spread of droplets, cutting down on some of the aerosols that we all spray out. I'm doing that right now except they're going on my computer rather than on a neighbor but I'm generating millions of little particles just by talking. And they can be infectious, so there's no doubt, and it's proved physically that these masks and respirators reduce what is coming through from what we exhale into the air around us. The N95 and KN95 provide protection for us - and if you're in circumstances like travel where you want to take steps protect yourself, I would advise using a true respirator N95.

You asked the question of does mandating use of masks make a difference, and I'll make one point first - it's very hard to evaluate and say "did a mask mandate make a difference" because there's so many other things going on. That said, there have been some good studies; there was a paper on school mask mandates in the New England Journal of Medicine within the year that showed that several communities that continued mask mandates when others dropped them did better. There's some controversy recently because the evidence was reviewed by a prestigious group called Cochrane, and this review was really misinterpreted and misrepresented. It didn't really shed light on the critical question: Did mask mandates make a difference during our COVID-19 pandemic? Without crystal clear evidence and some misrepresentation and misinterpretation, I'm afraid that the question of mask mandates has just become clouded - and of course politicized which just adds the difficulty of sorting out the science.

JK: I think fundamentally this is about protecting yourself and also protecting others. When we had a situation where there's a lot of uncertainty about how dangerous was this virus, how it spread, and what do we need to do about it I think appropriately public health officials took on a very conservative posture which is really keeping everyone safe. And if you did have COVID, wear a mask so you wouldn't be spreading it around. In many instances I think it makes sense to have a standard process by which we as a nation, we as a community, are given best practices.

For example, in our hospital it was a mask mandate - in fact I still have a mask mandate when I am in my pulmonary clinic. I have to wear a mask no matter what; if the patient's coming in with leg pain I have to wear a mask because you don't know who knows they may also have some other respiratory illness. Not only COVID but influenza or anything else in clinical settings there's certainly concern and potentially high risk of individuals who may be ill with respiratory conditions, including COVID. We still in hospitals have to wear masks. Now if you if you look outside our hospital, even within our university if you're in an office setting where there's no patient traffic we don't have to wear a mask at this point because we're in a situation where most of us or nearly all of us are vaccinated. The virus has also changed so we have a certain amount of immune protection at this point even if we were to get sick. I think the way to think about this is that at different points in time it makes sense to have a standard policy by which we as a society want to protect ourselves, and then as we learn more and as we become 'safe' in an environment, then maybe we have to rethink it and relax those policies. I think it's not really a yes/no, I think of "at that time did it make sense" and I'm on the side of public health. I'm on the side of protecting people from me and me also being protected from others, so I'm certainly a pro mask individual.

RH: I think you summed that up nicely - I also think it depends on the time and place. I think there are times and places now where masks still make sense for individuals that are at higher risk or if you know you're going to be in contact with those individuals - masks makes sense. I'm also thinking back to the late fall when we had not just COVID-19 circulating but RSV and influenza as well. Thinking about masks and those settings for other potential infectious diseases that are being transmitted - it comes back to the time and place. What I said at the very beginning about the response and the tools in our toolbox evolving over time and being different at different periods in time.

Public health communication challenges

KU: You have public behavior and the idea of communication and you can have both coordinated communication efforts that are really clear and transparent in a sometimes highly politicized world. In a way, this is what we know at the time, these are the best steps that we can take, and this may evolve and change over time. How do we as a society evolve that behavior when we know that it's really hard to shift and change large populations of human behavior. Some of that comes down to the messenger, how we're communicating, and how we're getting those messages out there - with those caveats or those nuances or the ability of putting uncertainty boundaries around things so that it becomes a little bit of that more nuanced approach. We have audience members who love to talk about this communication aspect - what has the public health field learned about effective communication measures? What are some lessons learned in that regard?

JK: I would say we need to use the most transparency possible about the uncertainty that we face at any given time when making decisions. The more we can be clear about what we know and don't know the better, and then our motivations for making recommendations for particular policies, both the pros and cons. So part of it is the message - are you being clear and recognizing there's an upside and downside to any particular policy or recommendation.

The second is the messenger. With the politicization of science and different people sharing different sets of facts, we don't have a common pool of information. Social media has been challenging because people are sort of in their own echo chambers listening to a subset of 'facts' being reinforced. So one is the message, but the second is (given the fragmentation and the segmentation of our population) who the messenger is which is as important as what the message is. We need to be very thoughtful moving forward about having appropriate trusted messengers in different communities. And when I say 'community' I don't mean just your zip code, I mean your bubble of social interactions.

The third is just recognizing that what we learn changes over time and to have an explicit statement that we're going to come back and revisit this together. So having a periodic update that allows people to recognize that this is not a one-size-fits all forever but at this point this is what we're saying. So in summary, I think being a little more comprehensive with the pros and cons and the uncertainty and why we're making a decision a certain way, really investing in trusted messengers of various types, and then recognizing that as something like a pandemic unfolds things change and you're going to have to revisit it based on all the things that are changing.

JS: I think everybody remembers March 13th - we all dashed out to the grocery store and bought food and toilet paper and when you've brought your groceries home you might have been washing them down or letting them sit for a day or two to decolonize. We had this idea that perhaps surface transmission was really important. I'm not sure why we got it so wrong for so long because clearly with this explosive pandemic, airborne transmission had to be critical to the story. I chaired a committee at the National Academies on providing respiratory protection to the nation and we emphasized a couple things and at the bottom was getting the right device into the hands of people when they needed it with information about how to use it. And that's a goal we haven't met yet and I'm afraid our report calls for so much to be done by our country that perhaps we will never build the framework until we start scrambling again if we face another pandemic or some other exposure for which we need protection.

I think what Jerry said is key - we have to reach to all the different groups we have to have the protection they need. For example, we still really lack what we should have for children, and the idea of being able to communicate with everybody regardless of education, language, or anything else is something we haven't achieved yet. A key lesson learned about a fundamental public health measure was we just weren't prepared to get it out there for everyone and communicated about. We need to be more ready for the next time and that's the kind of preparedness we should be working on now.

RH: I would just add from the state perspective that communication was central to the response in public health. We see risk communication as a public health intervention so just along the lines of providing vaccines and providing testing, providing information to the public is a public health intervention so that people have the information they need to make decisions for themselves and their families. In my role as the state epidemiologist one of my jobs was to try and translate some of the data and science on what we were observing and help people understand it. So you saw me with the governor and in various press conferences trying to deliver that data in a way that hopefully the public could consume that data and make decisions for themselves. Certainly we didn't do that perfectly but I think our goal was really transparency and ensuring that people had all of the same information that we had access to that we were using to make decisions on, whether that was in the governor's office or in at CDPHE.

JK: To build on this - communication is something that was certainly not high up in my training. I don't think I took a formal class in communication yet I see patients every day and I communicate to various groups. I'm here on your show today you know I've been in newspapers and I've been on TV shows, etc. So I think part of this is all of us in healthcare or perhaps with roles or responsibilities for public health may need to think very seriously about the science of communication. Maybe just a little bit of humility that it's more complicated than it seems when you communicate.

There are best practices that we should be learning from, and (this may sound obvious but) communication is not a broadcast. So we have to think a little bit about a bi-directionality of communication so that when we do talk about things the format in which it is delivered needs an opportunity for reciprocity so there's some exchange of information. We need to be sensing what people are taking away from that conversation and how might you engage in a dialogue. That's a little different than having an advisory statement for 30 minutes or a minute and then then you move on because we have no idea whether that was received and how it was interpreted and how it's being acted on. These are the things that maybe we need to rethink here. When we say communication what do we mean by that, and how do we know it's working, and how do we tailor it to the various communities that exist?

RH: You mentioned earlier that the messenger matters and that's absolutely critical. A focus of our health equity work during the response was identifying Community Champions, and we had Community Champion programs that we identified across the state to do outreach within their communities. Trusted voices that have relationships with people obviously makes a big difference when you have someone that is sharing information with a similar life perspective as you do. I think that is a critical part of the response and honestly I think it is something that we continue to employ. Our most recent response is our MPX response, where we were responding to a new emerging infectious disease, monkeypox. We took lessons learned from the COVID response and very quickly engaged the LGBTQ community in developing our outreach materials and speaking to the community and I think that made an incredible difference.

KU: What does equity mean in our response and in some of these disproportionate impacts? Dr. Herlihy, you were talking about those health champions and communicators that can help you connect with those communities that someone such as yourself or others may not have a relationship a connection with. How has that changed and shifted when we've thought about some of that disproportionate impact?

RH: We certainly had a focus on health equity, and health inequities or disparities are long-standing issues, but I think one of the things that the pandemic did was really shine a light on some of these problems and probably engage more people in broader conversations about the need to address inequities - long-standing inequities in our response activities. I'd mentioned that I think one of our more recent successes is doing that very early on in the response to mpox. Engaging our community and having those conversations because we don't all have the same life experiences and lived experiences to understand how messages are going to be perceived by different communities. So that has been something that's been elevated during the response and hopefully will be something that continues - that engagement with the community, that outreach work. Our division at CDPHE has a new Health Equity Group that we work closely with when preparing our responses or engaging the community and trying to understand the impact of various diseases.

JS: If you look across the course of the pandemic in Colorado the rates of hospitalization across the state are lowest in those individuals identified as white and those identified as Asians were even lower. Blacks, Hispanics, and American Indians remained at the top and fluctuate as to which group was at the top. There are many underlying reasons that include how much people are exposed - there were certain occupations where people did not go home and they stayed public-facing and were exposed more than others. Those individuals in the service industry and grocery stores and maintaining transportation for example. The impact of exposure was different and then the distribution of those conditions, which makes people more at risk for more severe disease also varied as did healthcare access. There's a lot of complexities here to sort out in terms of trying to do better next time and I think there's some clear lessons learned and lots of academic writing about these problems. Now we need to go on to the solutions.

Long COVID and other emerging diseases and viruses

KU: We've talked briefly about mpox - can you elaborate how some of our response to COVID 19 has informed the public perception and response of how we're dealing with potentially other emerging diseases and viruses? Let's go to that big theme: what are we learning here and how is this applying both in the field but also in the public perception as well?

RH: One of the things that I have noticed, mostly in the last year or so as public interest and media interest in COVID specifically has started to decline, I noticed greater interest than I recall pre-pandemic in infectious diseases. I think the public and the media understand infectious diseases and how they're transmitted and perhaps are more curious than they've been historically. The general population and the media seem much more interested in the work that we do now, and hopefully that's a good thing, in understanding how diseases are transmitted and prevented and then being engaged in the response with us. Definitely a substantial shift that I've noticed in the last years.

JK: I'd like to add to that - the other complement to this is a greater recognition that infectious diseases have a have a so-called acute phase when you initially get sick or infected with something and then what's called a post-acute phase or the chronic phase. The subsequent you know weeks months or years afterwards, which at least in in the COVID context is being called long-COVID in the lay community. In the scientific community sometimes it's called post-COVID or post-acute sequelae of SARS cov2 or PASC. A lot of terms are being thrown around right now but I think this recognition that infectious disease in some cases actually has a tail and that tail can be almost as bad or even worse in some cases than the acute infection, for example: polio. Polio had an acute phase where you might get sick and you may have some GI symptoms but some people then went on to have paralysis, couldn't breathe, and so forth, so there's this tail that became actually the real problem. Lyme disease is another example, a tick-borne disease that I'm sure folks in Colorado are well aware of. You might get a rash or you may have some acute symptoms, but then some people go on to develop neurologic problems, cardiac problems or other arthritis and other issues.

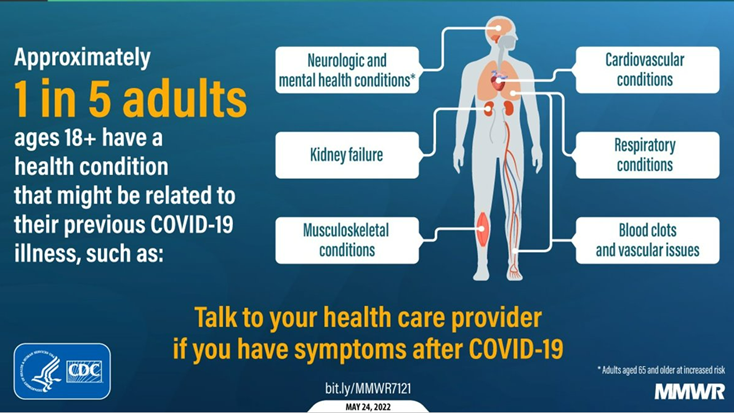

I think this is a perfect time for us to talk a little bit about what is long-COVID, what do we mean by that, and give a little explanation and continue. This (Figure 3) is a slide from the U.S Center for Disease Control, it came out in May of 2022 and this probably represents the best data in the world about what we're calling long-COVID. Long-COVID is essentially symptoms, signs, or conditions that exist at some time period after the original illness. Sometimes people use one month after the original illness, some people use three months, some people use six months - that's under some debate right now. When does that clock actually start for calling it long-COVID?

Figure 3

The U.S Center for Disease Control did a historic study - this data (Figure 3) is from two million Americans in 50 states where they looked at electronic health records of people who did or did not have COVID and then followed them for about a year in the electronic health record across the U.S. This was to say what are the conditions that seem to be popping up more in those individuals that had COVID versus those individuals who did not have COVID. The top line summary of all this, on the left-hand side of Figure 3, is that about one in five adults or 20% of people age 18 or above have at least one more condition than they wouldn't have otherwise had they not had COVID. This is observational data using what's in the electronic health records so it's the best estimate we have right now. If you look at the conditions that perhaps light up as being one of those extra conditions, first is that some people have multiple conditions not just one.

They looked at 26 conditions and all 26 of them lit up and it could be problems with the heart or what we're calling cardiovascular conditions. Fast heart rates or dizziness when you stand up - something we call postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Or you could have respiratory conditions. Could be cough, could be shortness of breath, or it could be some vague sort of chest discomfort. Some people have blood clots particularly early in the disease and that's a little bit less common now that we've seen this much later but certainly blood clots early after having an illness is more common. Also musculoskeletal conditions such as weakness or joint pain, or kidney problems. And in some cases just neurologic and mental health conditions. I'm sure people have heard of brain fog - the inability to concentrate, perhaps difficulty looking at bright lights or a television monitor, and then of course anxiety and depression. Anywhere in which there's blood flow, that part of the body could be affected and could take a long time. It could be even months or years afterwards.

Also concerning about long-COVID or post-COVID conditions is that although it's more common in people who are hospitalized for COVID, it can also occur when people have relatively mild disease and this is concerning because it means that we shouldn't just focus on people who had severe COVID. It looks like pretty much anyone's at risk and what we're learning is that it's not only the virus, it's the type of virus variant, the host response, your immune system's ability to fight the infection and keep it a bay and whether it appropriately turns off when it's taking care of the infection, and then finally how quickly you get care. Do you let your COVID get to the point where it gets serious? So this access to care or what you go about doing once you get health care access is important. In summary, long-COVID is essentially any condition that happens one month or longer after the initial infection. We now know it can affect any part of the body, and the best data right now is that one in five adults who've had COVID end up with an extra health problem that we're now calling long-COVID.

RH: As an epidemiologist my perspective here would be in trying to understand the scope of long-COVID and quantify how much long-COVID is occurring and there are many challenges in doing that. There's a new report out from the governor's office, the office of saving people money on health care here in Colorado, where we've done some work trying to estimate the burden of long-COVID here in Colorado. Honestly one of the fundamental challenges, which is now being addressed by the national academies, is trying to define what long-COVID is. As you just heard it is a wide-ranging number of syndromes that can occur and so defining it is the first step in trying to quantify and understand the burden that exists right now. That's one of the challenges in front of public health. First trying to understand the problem and then next is ensuring that individuals who are experiencing long-COVID have access to health care, whether that's specialized health care or ensuring that their primary care provider knows about long-COVID, and how to diagnose it and treat it. There's lot of the work that's happening right now both at specialty health care centers for individuals who may have more complex cases, but also just your average internist or family practitioner really needs to have a strong grasp of what long-COVID is to identify and treat patients.

JS: So far, long-COVID can only be as long as three years, and I think what's important from the research side is that we are geared up to continue to watch people at risk and understand what happens. For those who have it now to understand what its natural history is going to be. I know Jerry's involved in studies that are addressing this kind of question so we're just at the start and I think we need to make sure that we're watching carefully to see what happens.

JK: As someone who sees patients with long-COVID, I think the first is to validate the fact that there are some people that have not fully recovered or perhaps have new problems that they didn't have before. At the beginning of this nobody even knew of the potential for long-COVID so I suspect a lot of people were not believed you know either by themselves, their family members, or by their doctors. So the first is just to acknowledge there's a lot we don't know, but we do understand now and there is good information suggesting that this is a problem. It's a multi-system problem and it does exist so we're kind of in the descriptive components right now, counting how many of these cases exist, how do you define it and so forth.

The other component of this is that the federal government has put a substantial amount of resources in funding what's called the National Institutes of Health Recover Initiative, and that's a billion dollar program, the largest study that I've seen in 25 years in academia. They have centers literally coast to coast in the U.S (including two centers in Denver both Denver Health and the University of Colorado) that are part of this recovery initiative where we're not categorizing and describing it but we're studying the biology of it. Sometimes we call it pathogenesis - what's actually going on that's creating this problem. There's some serious scientific effort in a coordinated way across the country, and it's the first time I've seen this where we're all running the same study protocol and we're studying this in a very rigorous systematic way.

So the first thing is that we're counting it, the second is that we're putting a lot of energy in understanding the biology, and the third is about clinical trials for long-COVID. The reason I'm bringing this up is right now is that if you go on the internet you can find all kinds of home remedies and sometimes not-so-much-home-remedies - things you have to pay a lot of money for. I'm not so sure whether I would try some of those things because they seem a little odd and don't appear legitimate or credible. If you'd like to volunteer for studies, testing different treatments, these recover clinical trials starting are the opportunity for the public at large to feel that there's now a path forward about how to actually learn what does work and just as importantly what doesn't work.

Ongoing COVID surveillance and testing

KU: An audience member brought up a really thoughtful comment and question about how at the beginning of the pandemic we did see some critical failures in surveillance and testing and availability of PPE not only for healthcare workers but also for the general public at large. How is the supply chain response capacity geared up for potentially addressing these issues in the future?

RH: My perspective is more around the lines of how we've changed our data infrastructure and our ability to collect data and that has changed dramatically. Thankfully with an influx of federal resources we've been able to redesign our surveillance systems and we're actually in the process of doing some of that work now. So if you think back to before the pandemic to the types of communicable diseases that our team was investigating, they didn't happen on the scale of tens of thousands of cases. They were much smaller numbers and so we really didn't have the data infrastructure to receive the large number the volume of cases that we were seeing and process that data. I would say the same thing for our state public health laboratory. Their capacity has dramatically changed over time from the scale of running single digit number of tests in a day to being able to perform thousands of tests. It's been a dramatic change in infrastructure and we're certainly hopeful that the investment in public health is going to continue into the future

But one of the things that we've experienced with public health emergencies in the past is these large sums of funding that come to public health - but they're often siloed funding. They're specific to a given disease and then we see resolution of that disease, but then we have a new emerging infection that comes up like mpox or a new type of influenza or whatever it might be and those dollars that public health has received are very siloed and unfortunately can't be used broadly. A lot of work has gone into improving public health infrastructure but that work needs to continue and needs to be less categorical than it has been historically, because unfortunately public health has been underfunded for decades and decades. That was unfortunately apparent at the beginning of the pandemic in our ability to scale rapidly.

JS: I think we both need to do better on the preparedness side but we also need to rebuild. And I think both have to go on and of course both take funding and there's various task forces and reports calling for transformations. A lot of emphasis on data and as Rachel commented, the response needs to have a longer term view than we usually have after this kind of circumstance, and let's just hope that that happens.

KU: What about monitoring other emerging zoonotic diseases? Is monitoring being effectively done and have we seen an increase in that?

RH: Even before the pandemic there was an increasing emphasis on something we call One Health, which is this recognition that animal health and human health are very intertwined. We know that a number of infectious diseases can emerge out of animal populations; that's the classic model for influenza that we think about and lots of us have seen reports about avian influenza in the news recently, so certainly investing in the public health infrastructure that lives at that interface between animals and humans is critically important for us to be able to detect emerging infectious diseases early and respond to them. Recognizing that ensuring that animals are healthy is critical for ensuring human health as well.

Trust in public health and science

KU: Final question, and your answer can be a personal reflection of yourself or a reflection on the public health field at large. Please talk about trust in public health and medicine, which has taken a beating, and whether it's been loss of trust based on political divides or whatever sort of factors could play into that. I'm curious whether you personally or as a field have had any reflections on where there has been a misstep and an opportunity for personal learning and growth as a field or as an individual. We know there has been some harm done in that trust and the idea of needing to rebuild some of that is important.

JK: I think that as a university, we're thinking more broadly about our role in the ecosystem of trust and I think recognizing that most of the difficult things that have happened with COVID have moved at the speed of trust. This is probably not the last time we're going to see some version of this so we've put a lot more energy on building community partnerships and having a reciprocal relationship where we're bringing value in a bi-directional way, involving them more in our activities, spending some time outside of university walls, and really thinking more about relationship building more broadly. We don't know when the next issue is going to be or what specific problem it is, but if you already have a relationship to build off of you're going to be that much further ahead.

JS: As someone who trains who will go out and do research in public health practice, in public health led policy, and public health, I think this is really important. Trust in this field and other fields of science has been eroded - I mean The Institute of Science & Policy has part of its purpose sort of directed at assuring trust in science and what we know. I think we face a new challenge, and it's ever more acute, and that's the rapid spread of incorrect, misleading, and potentially harmful information. That has really threatened some basics of public health and I think those of us in public health need to understand how to deal.

I'll sort of analogize with the threat of emerging viral misinformation and how do we contend with it and certainly COVID-19 is not the only example of this being a problem. We have those who are deliberately disseminating wrong information, let's call that disinformation, and sometimes with pretty base motivations like selling a product that doesn't work or some other sort of self gain. We in public health need to know how to deal with that - those who have politicized and chosen to attack public health measures or public health personnel for their own gain. That's unfortunate and it has consequences that have been realized and can be demonstrated in mortality figures. We have work to do there and I think that does go back to learning how to communicate perhaps more powerfully and communicating at the right time. It's a risky business, it takes work, and there may be counters but I think it's important to continue to place what we know in front of the public and admit what we don't know.

RH: I think for me, that was in sharing data and information for individuals to make decisions, but when it comes to lack of trust I think there's probably a lot of work for our academic partners to do to understand where that lack of trust is coming from. There are certainly things that we recognize and we know we need to work on. Some of the health equity work that I mentioned but also there's also a lot we don't know about where lack of trust in government or public health is coming from. I think there's a lot of work in front of our public health academic partners to try and understand them and help us be prepared in the future.

KU: I want to say thank you, Jon, Rachel, and Jerry. Thank you for your service, your dedication, and your leadership - as well as to the entire field of public health. You all have given a lot of blood, sweat, and tears getting us through this pandemic as far as we are. Thank you for sharing some of your thoughts and reflections. I think taking some of those critical hard looks is always a great way to learn and move forward

Disclosure statement:

The Institute for Science & Policy is committed to publishing diverse perspectives in order to advance civil discourse and productive dialogue. Views expressed by contributors do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, or its affiliates.