COVID-19: Six Months In

This article is part of an ongoing collaboration between the Colorado School of Public Health, the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, and the Institute for Science & Policy. Watch the full recording of this session and find all of our previous COVID-19 webinars and recaps here.

By mid-March, the ongoing spread of COVID-19 began to affect American life in a big way. The NBA suspended its season. Flights, concerts, and conferences were abruptly cancelled. States began to implement full or partial closures of non-essential businesses. Scientists and public health officials raced to issue guidance, even as much about the disease remained unknown. Now, six months later, our collective knowledge of SARS-CoV-2 has evolved dramatically, both from an epidemiological perspective and a societal one. What have we learned so far about the effects of policy, the speed of research, and public trust in science that could help us in 2021?

Georges C. Benjamin, MD, Executive Director of the American Public Health Association, stopped by to highlight big picture lessons from the pandemic so far - including early missteps and ongoing course corrections that will likely shape the course of the coming year - and the broader role of public health in our society.

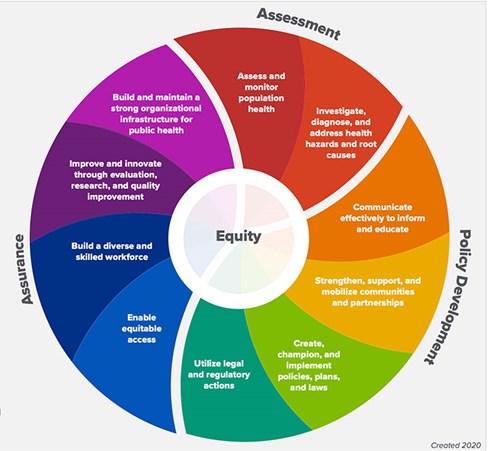

Public health performs 10 essential services

Everything we do in public health is about assessing the community, understanding what's going on, getting the data, monitoring population health, and investigating and diagnosing what's going on. It might start with a single case, but as you know, often it becomes large numbers of cases. And then we craft policy to address policy problems with regulatory activities. We search for solutions by communicating effectively to inform and educate by trying to mobilize communities, getting political support, getting community support, and creating champions to support the policies and procedures that we use.

Using persuasion and policy

Let me just remind folks of the very famous story of John Snow, [the English physician] who, in order to quell a cholera outbreak, was able to convince the city leaders to take the well pump out of the park where he thought people were getting contaminated water to drink. Now, he did not go out in middle of the night with a wrench and take the handle off. He had to convince the city leaders to do that. He was able to do that in a very religious time by convincing one of the religious leaders to support his position. So in many ways, he did everything in these essential services by assessing and understanding what was going on. He thought about what he had to do from a policy perspective. He had to figure out how he got them to basically pass a referendum about clean drinking water. And then he actually made sure the pump handle came off. So politics does play a role in everything.

No news is good news (sometimes)

In public health, we often say that our best work is done when nothing happens. And that's our goal. Our goal is for things not to happen in the first place, to mitigate them in such a way that we forget that they happen.

Politicization of public health measures and early missteps

With masks, the early wisdom was that the masks would not protect the general public from a droplet infection, which is the primary mode of COVID transmission. We were told that masks don’t fit tightly enough, that we want to save the N95 masks for healthcare providers. It got politicized. It became a blue state and red state argument. It became a ‘I believe in COVID’ versus ‘I don't believe in COVID’ argument. It was came out as ‘you told us one thing and then you told us something different.’ And that was just very poor risk communication.

There was also this idea that the economy has to be preserved at all costs and that health is not as important. But the secret to preserving the economy is to protect health. And I remind people that health is 18% of the gross domestic product. So, we are already into the economics of the country by virtue of our health system. And the best way for us to get out of this pandemic is to focus on health solutions.

On crisis communication

We have seen some good communications work from the governor of Ohio and the governor of New York. Tony Fauci is the gold standard in terms of telling us what he knows. In the old days, which was not too long ago, we used to have daily briefings in crises like this for infectious diseases from the CDC, and they would come up every day and they would say, look, this is what we notice, we learned something new today and here's why we're changing what we told you. So that people get a sense that we're not, you know, shooting from the hip, that we have a rational reason for doing something now. People may still have the right to disagree, you know, but they don't have the right to be disagreeable, and they should argue their perspectives.

But that's not what's happening. The CDC is putting a lot of really good science guides on their website, but they’re kind of just being posted, just kind of stuck there. Normally they would say, okay here's what we think and here's why we think it. And sometimes that public debate results in changing the governance, and that's good. That’s not what’s happening now.

Inequities of the pandemic

The biggest thing that surprised me was that the health inequities have been so profound, even though its true of many diseases. Even I was surprised at the degree of illness and injury that has occurred from COVID in some communities. All the white collar workers that have computers can work from home. That's great, but bus drivers, sanitation workers, meat plant workers…those folks are out and about. Essential workers are much more likely to get exposed. Secondly, there were a lot of delays in actually sheltering in place. There were some terrible rumors that African Americans, for example, were immune from this disease. That was going to social media and leading to misunderstanding.

Another example is drive through testing sites. If you didn't have a car, and you're not feeling well, taking a train or a couple buses and then walking a few blocks to go get tested wasn't enough. And if you didn't have a car, sometimes getting the test was not an option. So the structure of our early testing activities was flawed. There have been efforts to move testing into communities of color, into low income communities. We've always known you have to open up the testing sites on weekends, and after hours. We have to acknowledge that many of the people that are at highest risk are shift workers.

On resources and supply chains

I think there was a lot of work done by the healthcare community to figure out how to share resources. The downside is they shouldn't have had to do that, shouldn't have had states bidding against one another for equipment and supplies. They weren't designed to do that. We could have done that at the national level much more effectively. I understand there was a reluctance of the federal government to get in that space. But that was ill conceived thinking. And I think not having a unified voice is a real problem

We could turn the corner today and begin to do things in the manner that we know works. Put the CDC out there in the lead, unbridled. Let them give us press conferences every day. Stop being afraid of what they're going to say and worrying about the impact on the economy. The stock market is quite resilient. But the faster we get our hands around this epidemic, the faster we're going to be able to return to a near normal status, even though it’s never going to be like it was a year ago.

Vaccine development

I do think that the vaccine is a game changer in terms of function in our daily lives. Let me let me talk about what we need to do this fall. First, we have to recognize that we're about to get hit with the annual return of influenza. The good news is that wearing a mask, washing your hands, and keeping your social distance is also a good strategy for influenza. And so many of the things that we do for COVID will help us reduce the impact of influenza and in fact that has been the experience of the Southern Hemisphere, where they had a relatively light influenza season, but only because they did all of those things. So people should get their flu shot. This time next year, we'll still be wearing masks, washing our hands, and keeping our distance at some degree. Next year’s return to school and return to sports will be very different, but still measured.

An emergency use authorization allows you to use a medication of label before it has gone through the full process of the Food and Drug Administration's regulatory aspects. It means that they are, in effect, accepting the word of the pharmaceutical company, that they have done all the right things to ensure that a drug is safe. The best way to do this is to go finish all the vaccine trials and make sure that the trials have been done as designed.

Assessing the national response

On a scale of one to 10, you know, we're somewhere around a 3. And how do we get to be 10? We get to be 10 by having a unified national voice, putting together a strategic plan, and allowing the science and medical personnel to talk to the American people to provide the political leadership that this outbreak deserves. And then as we look forward, we're going to have to build a public health system that we can truly be proud of that can identify new threat characteristics.

There’s been some research that the average American can't name a living scientist. Let me tell you: Science is done in your academic health centers, in your community, in your museums. It's done in your health department and in your doctor's office. They're the doctors and nurses and they're the chemists and biologists in your community and in your neighborhood.

Executive Director, American Public Health Association

Disclosure statement:

The Institute for Science & Policy is committed to publishing diverse perspectives in order to advance civil discourse and productive dialogue. Views expressed by contributors do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, or its affiliates.