How Cities Can Create Circular Technology Supply Chains

When the US Senate recently passed the Inflation Reduction Act, $370 billion was earmarked for the application of cleantech. With a flick of the pen, the Biden administration sped past Canada, my home nation, in terms of investments in reducing pollution. Now spending three times more per capita than Canada, the US is taking a lead in climate change preparedness.

According to USA Today, in 2017 Canada had the highest overall waste production per capita in the world at just above 36 tons per person. For reference, in the same year, the US total was 25.8 tons per capita (good enough for 3rd worst contributor). When looking specifically at e-waste, Canada dumped 147 million metric tons of e-waste in 2016. Canada’s relatively small size but high income means its per capita dumping is extremely high. The backbone of Canada’s economy, resource exports have grown by 34% from 2020 to 2021. These resources include minerals like copper and gold that go into consumer electronics and pollute our Earth. Northern Ontario is a hotspot for resource extraction and where the consumer electronics supply chain begins. They then head off to manufacturing hubs in Asia for assembly, and back to Ontario in the stores that line Toronto’s streets. Post-use, the now e-waste is either sent to dumping grounds in southern Ontario and Michigan or ‘recycled’ back to Asia to be taken apart by informal recyclers. As one of the largest players in the consumer tech supply chain, Canada should be at the forefront of e-waste recycling. Making sure their resources are reused, reducing waste, and saving on emissions from extraction.

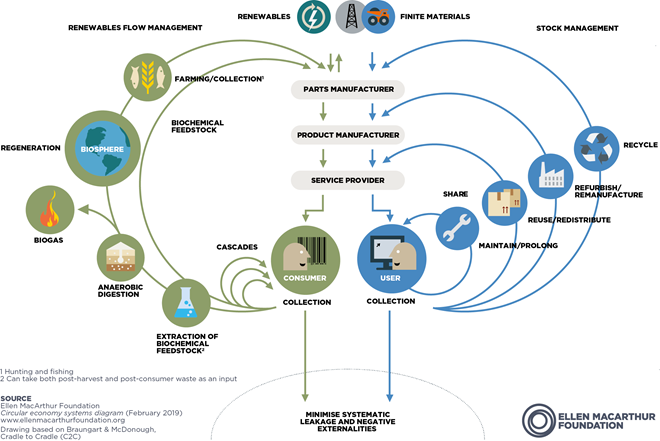

What some might find surprising is that China is revolutionizing how we treat our e-waste. Both the manufacturer and recycler of goods, China is the largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world but has spent the past decades as the world's top recycler. Taking our e-waste, stripping it for parts, and putting those inputs back into their manufacturing ecosystem, China has built a circular economy around its consumer electronics industry. Western cities can learn a lot from how the Chinese megacity Shenzhen has built itself a sustainable supply chain for the future of the tech city. The e-waste ecosystem in Shenzhen, and wider China, naturally takes advantage of circular economic principles. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, a circular economy refers to a model that:

“Reduces material use, redesigns materials to be less resource intensive, and recaptures “waste” as a resource to manufacture new materials and products.”

Ellen MacArthur Foundation; Circular economy systems diagram (February 2019); www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org

How Shenzhen built itself, and everything else

The story of Shenzhen, a remote fishing village in southern China, starts with its designation as a special economic zone in 1979 by the then-new leader of the People's Republic of China Deng Xiaoping. As a special economic zone, Shenzhen was opened to foreign investment and expertise, a new possibility in communist China. By investing in physical infrastructure, the government was able to attract large businesses like Apple, HP, and others. Over the years, Shenzhen has become China’s and the world's technology one-stop shop. It is estimated almost 90% of the world's consumer electronics are made in Shenzhen. And that was just yesterday's Shenzhen. Nowadays, the city acts as a knowledge and industrial hub. With local companies like DSI and Huawei headhunting the best talent, and factories in the suburbs still producing low-cost components like circuit boards, Shenzhen does everything in the technology supply chain.

Such a concentration of consumer product manufacturing means Shenzhen produces tons of e-waste. In 2010 China produced e-waste totaling 2.3 million tons. Once the largest importer of waste, Chinese laborers would recycle the thrown-away consumer electronics they produced. The importation of e-wastes from developed countries to China was about 1.5 million tons in 2001. Due to adverse health and environmental effects, the government declared it was no longer willing to accept foreign garbage in January 2018. But thanks to the built-out e-waste recycling system, cities like Shenzhen can handle their growing domestic e-waste.

How China is managing its e-waste

With its global dominance of electronics, China handles the production of consumer electronics through its many factories and companies, and distribution through its impressive physical infrastructure. And while still largely informal, the country takes care of the e-waste too. According to Lin Wei at Peking University, China has several ways of using its e-waste: using it as electrical and electronic products that might enter the second-hand markets; donating it to poor people in western China, and recycling obsolete appliances by private companies for raw materials.

Each of these methods brings ‘obsolete’ consumer tech back into the supply chain. Either to be reused or re-integrated. Based on current projections, the e-waste recycling potential in China is expected to reach $73.4 billion US dollars by the year 2030. This is turning e-recycling into a lucrative market for everyone. With less than twenty-five percent of e-waste being recycled in China (formally at least), there is room for growth, domestically and globally. And Shenzhen has the blueprint.

Since 2017 the World Economic Forum has worked with partners to launch and deliver a multi-stakeholder project, Circular Electronics in China. The project was formed as a collaboration platform between industry, government, and academia to reach the Chinese government’s ambitious circular economy targets of recycling 50% of e-waste by 2025 and including 20% of recycled content in new products. Shenzhen, with its localization of industry, academia, technology, and recyclers, is a leading space for innovators to find new solutions.

A circular business model is one where businesses recover or recycle the resources used to make their products. Expanding that concept to supply chains, a circular supply chain would involve a network of organizations and people that lifecycle a product from resources to product to waste, and back to life with recycling and repurposing. Involving physical and knowledge infrastructure, the circular supply chain in Shenzhen is well-built.

Not a perfect process, the tech supply chain of Shenzhen has taken steps to introduce a circular economy, and now is the time we in the West embrace that idea too.

Supply chain crises

The growth of neoliberal globalization has led to an explosion in trade.

Take your average consumer electronics, and it is now made with pieces from around the world. A complicated organism, any disruptions in the supply chain topple the whole system. That is our current problem as supply chains are in shock from the effects of the pandemic and other causes.

An article by the Washington Post interviewed 50 stakeholders in the supply chain on just how big the infrastructure problem is, mainly in the US but also in most western countries

“The pandemic exposed weaknesses in the nation’s transport plumbing: investment shortfalls at key ports, controversial railroad industry labor cuts, and a chronic failure by key players to collaborate, according to interviews with more than 50 individuals representing every link in the nation’s supply chain.”

Building out better domestic supply chains can reinvigorate the manufacturing industry at home and provide insurance to consumers when global incidence leaves supply chains vulnerable. Using recycled materials and goods can alleviate the need for importing resources like tin, cobalt, and copper. But adding circularity is not an easy process. According to the Harvard Business Review:

“When products have relatively low value, companies—even very big ones—may need to find partners to make circularity work.”

The quote highlights the need for collaborative networks between manufacturers, communities, knowledge industries, and governments. A progressive and environmentally conscious country, Canada has the will to change, and now we have the way.

The new circular supply chain

By applying circularity, cities and regions can reach net-zero without economic calamity. Building out industries and start-ups around circular principles, and redistributing our physical infrastructure, can grow economies sustainably and equitably.

Let's look at the three factors we need for our circular supply chain: the knowledge economy, the manufacturing economy, and the recycling economy, but in my hometown of southern Ontario.

Knowledge Economy → Recycling Economy

Southern Ontario has many high-level universities capable of providing intellectual capabilities to improve the recycling process. The University of Toronto, McMaster University, and the University of Waterloo are all located close to population centers and recycling facilities. Recycling e-waste infrastructure needs recovery infrastructure, the physical and logistic connections between consumers' thrown-out electronics, and the processing facilities. With the help of electronic device collectors, a whole industry could be set up to collect electronics and give them to recycling centers.

A simple example of this comes from the food packing industry. The Australian food-packaging company BioPak introduced a composting service extending to more than 2,000 postal codes across Australia and New Zealand, in partnership with local waste-management businesses. Customers can toss compostable packaging together with food scraps directly into an organic-waste bin for collection. BioPak claims that 660 tons of waste have been diverted from landfills because of the service.

Recycling Economy → Manufacturing Economy

Taking recycled material back into the manufacturing process means receiving inputs and creating products that have value to the market. Some industries have better economic capabilities when it comes to circular products.

“A circular business model is sustainable only if the value can be economically recovered from the product. It might be realized through reusing the product, thereby extending the value of the materials and energy put into the manufacturing process, or by breaking it down into components or raw materials to be recycled for some other use,” according to the same Harvard Business Review article.

Companies like EcoWatch Waterloo already collect, repair, and refurbish e-waste. Small in operations, connecting these recycling companies to retailers would improve their consumer base. With metropolitan areas like Toronto, Montreal, and New York within the vicinity, faster road and rail connections would scale the number of refurbished goods going back to consumers.

Breaking down e-waste material is an energy-intensive process, but so is regular resource extraction. Recycled materials like aluminum will save money equal to 90% of the energy costs it takes to extract the same cubic feet of material. As energy prices increase worldwide, a domestic e-recycling market can be profitable. Profitability is the only surefire way to get business on board.

Increasing southern Ontario's green energy capacity will improve businesses’ ability to reproduce recycled goods. And building large-scale green energy infrastructures like wind turbines and nuclear plants makes sense in a region with high populations

Manufacturing Economy → Knowledge Economy

As a major resource exporter, Canada produces large amounts of greenhouse gases. Removing resources from discarded products and putting them into new products will reduce the need for constant extraction, popular in northern Ontario. Already a hub for material sciences, organizations like the University of Waterloo Industrial Ecology Group can help companies do so through cutting-edge research. The result of such connections leads to improved efficiencies with large corporate buy-in. This was done in 2018 when Apple introduced Daisy, a robot capable of disassembling up to 200 iPhones an hour to recover valuable materials such as cobalt, tin, and aluminum for use in brand-new phone components.

The Environmental Protection Agency released findings that show the magnitude of economic benefits that comes from e-waste recycling. The 2020 Recycling Economic Information Report shows that recycling and reuse of materials create jobs, while also generating local and state tax revenues. In 2012, recycling and reuse activities in the United States accounted for 681,000 jobs, $37.8 billion in wages, and $5.5 billion in tax revenues. This equates to 1.17 jobs for every 1,000 tons of materials recycled.

Providing green jobs and a domestic circular supply chain will assure informal markets in China and Thailand stop and join the safer and more formal recycling system. Keeping each stakeholder honest, government policy can expedite profitability with incentives like tax rebates. From paying good wages to re-investing in local economies, domesticating e-waste can have an incredible impact on our city, global community, and on our climate.

Writer and Researcher - www.likamk.com

Disclosure statement:

The Institute for Science & Policy is committed to publishing diverse perspectives in order to advance civil discourse and productive dialogue. Views expressed by contributors do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute, the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, or its affiliates.